James N. Carder

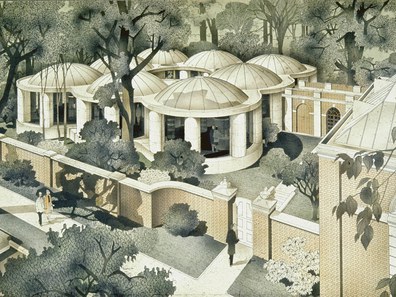

The year 2013 marks the fiftieth anniversary at Dumbarton Oaks of the Robert Woods Bliss Collection of Pre-Columbian Art. It also marks the fiftieth anniversary of the completion of Philip Johnson’s museum pavilion, the architectural masterpieceIn the American Institute of Architects guide to architecture in Washington, D.C., Gerard Martin Moeller, Jr., writes: “Philip Johnson has produced a few masterpieces. The Pre-Columbian Museum is among them.” G. Martin Moeller, Jr., AIA Guide to the Architecture of Washington, D.C., 4th edition (Washington, D.C., 2006), 238. that he designed to showcase this collection (fig. 1). Both opened to the public on December 10, 1963: the Bliss Collection to widespread acclaim; the Pre-Columbian Gallery to generally positive, although somewhat mixed reviews. Both are now internationally famous. The Bliss Collection is revered for its high quality and its early promotion of the aesthetic importance of ancient American art. The gallery is now seen as a seminal building in Johnson’s late-1950s sea change in architectural thinking from International Style modernism to postmodern classicism. Since its opening in 1963, the Bliss Collection has been thoroughly researched and published in several impressive catalogues. Handbook of the Robert Woods Bliss Collection of Pre-Columbian Art, introduction by Michael D. Coe (Washington, D.C., 1963); Supplement to the Handbook of the Robert Woods Bliss Collection of Pre-Columbian Art (Washington, D.C., 1969); Elizabeth Hill Boone, ed., Andean Art at Dumbarton Oaks (Washington, D.C., 1996); Karl A. Taube, Olmec Art at Dumbarton Oaks (Washington, D.C., 2004); Susan Toby Evans, ed., Ancient Mexican Art at Dumbarton Oaks, Central Highlands, Southwestern Highlands, Gulf Lowlands (Washington, D.C., 2010); Joanne Pillsbury, Miriam Doutriaux, Reiko Ishihara-Brito, and Alexandre Tokovinine, eds., Ancient Maya Art at Dumbarton Oaks (Washington, D.C., 2011). The Dumbarton Oaks Pre-Columbian Gallery, on the other hand, has been little discussed or studied.See Bibliography. The architect Mark Wigley, Dean of the Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation, provocatively offered a psychological interpretation for the lack of scholarly interest in the Museum of Pre-Columbian Art, as the building is usually named in the literature. He wrote: “Our fear of this work, and I believe it is a fear, is a fear of seduction by that which lies just outside the rules, outside the law.” Mark Wigley, “Reaction Design,” in Philip Johnson: The Constancy of Change, ed. Emmanuel Petit, with foreword by Robert A. M. Stern (New Haven, 2009), 217. Wigley’s comments are quoted more fully at the end of this publication.This anniversary year provides an excellent opportunity to commemorate the collection’s impressive housing—arguably a work of art in its own right.

Preface

Since the date of this study, which was first published in 2013 in honor of the fiftieth anniversary of the Dumbarton Oaks Pre-Columbian Gallery, Philip Johnson’s history of bigotry has come to the fore and his name and reputation have been tarnished by his unsavory ideologies and associations. This preface, written in early 2021, serves as an addition and corrective to Johnson’s biography as outlined in the following chapters.

Chapters

The Robert Woods Bliss Collection of Pre-Columbian Art

Robert Bliss concentrated on building his Pre-Columbian art collection largely after the transfer of Dumbarton Oaks to Harvard in 1940. Over the next two decades, he would carefully edit and refine the collection, which was on display at the National Gallery of Art from 1947 to 1962.

Planning the Museum Addition, Phase 1

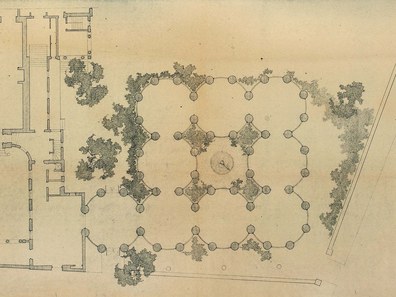

In 1958, the Blisses revisited the idea of a museum addition to house everything that was not currently on exhibition, including the Garden Library and the Pre-Columbian art collection. Plans submitted during this period offered very different visions of the new museum spaces.

Philip Cortelyou Johnson was 53 in the summer of 1959 when he began work on the Dumbarton Oaks museum wing. He was also at a turning point in his architectural career, both ideologically and stylistically, and was entering a new phase.

Philip Johnson and the Art Museum

In his design of the Munson-Williams-Proctor Museum of Art, which stressed enclosed, compartmentalized spaces, Philip Johnson signaled his first movement away from the influence of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and the International Style.

Planning the Museum Addition, Phase 2

During a period of eighteen months in 1960–1961, aspects for the final plan of the Pre-Columbian Gallery were worked out, including siting and the landscape, connecting the gallery to the existing structure, and construction costs.

Design modifications, including the size of the gallery, lighting, and materials, were made in 1961. By early 1963, the gallery was nearly finished except for the installation of the collection.

Last Concerns: Installation of the Collection, Landscaping, and “the Acoustical Problem”

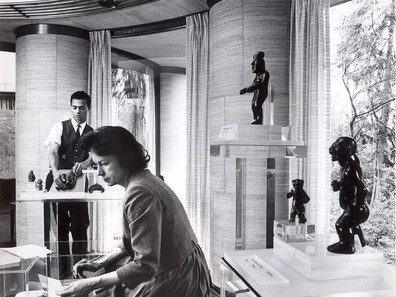

As construction of the gallery and installation of the collection neared completion, attention turned to the display of objects, the relationship of interior spaces to the exterior plantings, and an echo in the domes.

Critical Appraisal of the Pre-Columbian Gallery

After the gallery was opened in December 1963, journalists, architectural historians, and architects who reviewed the building were fairly consistent in their opinions and in their praise, although some questioned whether the gallery competed with the collection.

The Pre-Columbian Gallery as Postmodern Design

As early as 1964, several art critics, as well as Philip Johnson himself, used the term “postmodern” to describe the design of the gallery. In its reinterpretation of familiar historical styles and harmonization of architecture and environment, the gallery fits precisely this postmodernist definition.

Philip Johnson and Mildred Barnes Bliss

In the designing of the Pre-Columbian Gallery, it had been Mildred Bliss who had worked closely with Johnson to attain a shared goal of perfection, accepting his vision that it should be a modern building and critiquing plans and details to ensure its success.

After its completion, the gallery was largely overshadowed by other designs. Recent work, however, has reappraised its place in Philip Johnson’s architectural legacy.