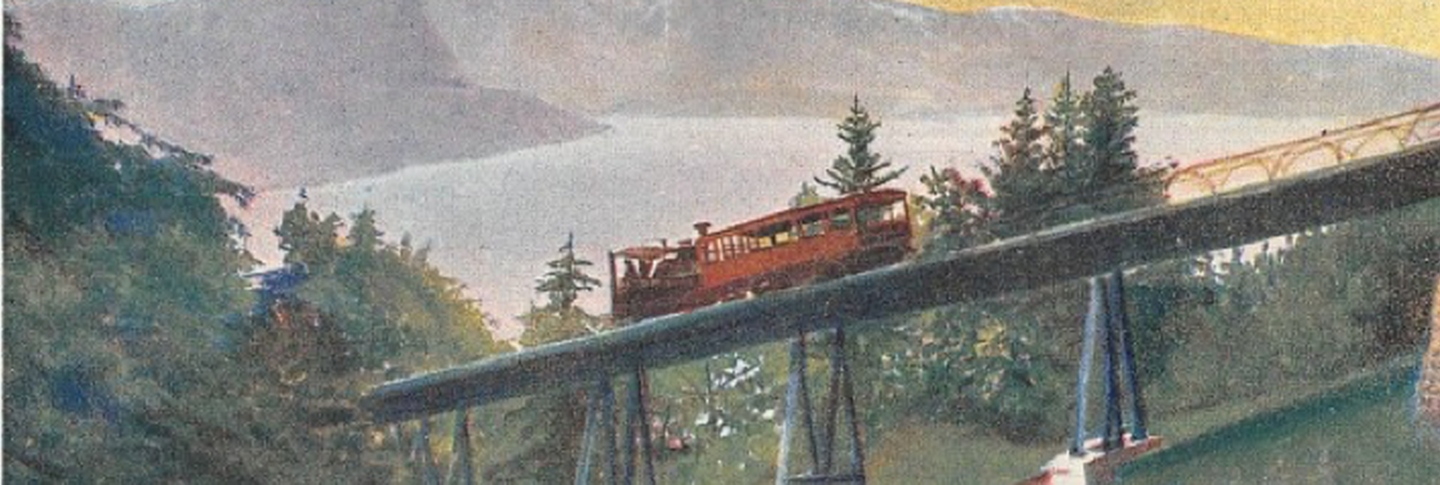

While vacationing in Europe during the spring of 1900, the English journalist George Sims decided to scale Mt. Rigi. At nearly six thousand feet, the massif offers a stunning view of the surrounding Swiss Alps. A railroad track, added in the nineteenth century, allowed foreign bon vivants like Mr. Sims to ascend the peak and enjoy the mountain scenery with minimal exertion. Sims boarded the train and went up with “a large party” of vacationing Europeans. Regrettably, the splendor of the vista seemed entirely lost on Sims’s traveling companions. He recounted the scene with annoyance in The Referee, an English newspaper: “Directly we arrived at the summit, everybody made a rush for the hotel and fought for the postcards. Five minutes afterwards, everybody was writing for dear life. I believe that the entire party had come up, not for the sake of experience or the scenery, but to write postcards and post them on summit.” The frenzy atop Mt. Rigi was hardly unusual. Unfortunately for the loftier-minded Sims, this was the nature of travel during Europe’s “postcard craze.”

In 1900, George Sims joined a growing chorus of writers perplexed and alarmed by the continent-wide mania for postcards. Reading their accounts today, one cannot help but experience déjà vu in chronological reverse: swap postcards with Facebook or Instagram, and the past begins to sound eerily like the present. Sims sneered at tourists for mobbing the postcard stall and neglecting the natural beauty around them; modern critics chastise travelers for viewing the world through a perpetually raised (usually smartphone-mounted) camera lens. Just as Sims held aloft the value of the “experience,” one does not lack for recent articles—often written by repentant social media fanatics themselves—that extol the virtues of unplugging, disconnecting, and “living in the moment.”

The picture postcard, although hardly an object of obsession today, once occupied a niche filled more recently by Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. There is an obvious similarity in function: to borrow terminology from the tech world, postcards allowed users to share experiences with long-distance connections through their innovative image- and text-based platform. There are deeper similarities too, in the ways that both can hijack our minds and shape our culture. Many of the same obsessions and anxieties triggered by the postcard craze have resurfaced with the rise of digital social media. If we wish to understand our own personal and troubled relationships with social media, we might gain some much-needed perspective from a look at the postcard craze. It was after all, the moment when Westerners first became addicted to the simple but ensnaring pleasure of “posting pictures.”

As an episode in popular history, the postcard craze has largely been forgotten. The picture postcard of today offers few hints of its erstwhile glory. In the first decade of the twentieth century, however, postcards were an inescapable feature of daily life. “[The postcard] takes possession of everyone, penetrates everywhere,” wrote Charles Simond in France. “The palaces of kings are as open to it as the humble cottage; it has loyalists in the city and in the village; all resistance is in vain.” This was in 1903, the same year that Germany broke all records and sent over one billion postcards through the mail. The numbers and ubiquity of cards only grew with time. George Sims, who decried the postcard stall atop Mt. Rigi, found no respite elsewhere: “Wherever you go, picture postcards stare you in the face. They are sold at cigar shops, libraries, chemists, and fruit stalls; they are arranged on stalls and every table at the restaurants; they are in the halls of hotels; they are in railway stations.”

The most popular cards, then as now, featured photographs of tourist destinations. The postcard that may be credited with starting the craze debuted at the Paris Exhibition of 1889, celebrating the recent completion of the Eiffel Tower. The newspaper Le Figaro began selling and posting souvenir postcards from the top of the tower, a winning combination that granted tourists excitement, novelty, and no small amount of bragging rights over their more earth-bound friends. Other tourist destinations soon followed suit, reproducing famous monuments and views. However, turn-of-the-century postcards boasted more versatility than their modern-day descendants: people sent cards featuring actors and actresses, works of art, jokes, insults, professions of love. Those who happened to own cameras could even print and send their own personalized cards. Senders often included short, telegraphic messages to their recipients: “Hugs and kisses”; “Am ‘OK’”; “Sending love,” occasionally giving more detailed updates to their status.

Postcards were among the most convenient ways to keep in touch at the turn of the century. People communicated over vast distances via postcard, bypassing the formalities of letter writing and the hassle of telegrams and phone calls. Travelers could share snippets of their experiences as they happened—thus evincing cultured and adventurous lives. Postcards did not always offer an accurate reflection of foreign locales (many featured photos colorized with garish and inaccurate hues, not entirely unlike Instagram’s popular filters), but this fact caused little to no alarm. Even if one’s postcard captured only a glimmer of the lived experience, it was enough to send a picture and say with confidence, “I have been here.” In many cases, postcards served simply as a convenient way to exchange greetings and plans. “Baby's arrival, his first tooth, his first trousers, his first bicycle, his first girl and his first baby, all go to the family circle by souvenir postal,” wrote one commentator. “Thanks to it, we know more than we once did about our relatives and friends, as well as about Burn’s house and the catacombs of Rome.”

As the postcard industry spread its tendrils into daily life, a now-familiar barrage of criticisms followed. Nowhere do the similarities between postcards and modern social media appear more sharply than in these anxious analyses. In his extended criticism of the postcard craze, George Sims lamented the deleterious effect postcards had on social interactions. “You enter a railway station,” he wrote, “and everybody on the platform has a pencil in one hand and a postcard in the other. In the train it is the same thing. Your fellow travelers never speak. They have little piles of picture postcards on the seat behind them, and they write continuously.” Another commentator sneered at the typical German traveler, whose “first care on reaching some place of note is to lay in a stock [of postcards] and alternate the sipping of beer with the writing of postcards. Sometimes he may be seen conscientiously devoting to this task the hours of a railway journey.” One writer freely admitted to this practice, describing himself with a heap of amusing postcards on the train, “muttering over them as if I were an incipient madman.” As with modern complaints against cell phones and social media, such critiques rested on an assumed bygone era of gregarious strangers and lively train-ride conversations, all of it spoiled by the siren song of handheld images.

Many commentators feared that the postcard’s popularity spelled doom for written communication as well, echoing modern worries over text-speak and Twitter’s character limits. A 1910 article in American Magazine made this grave claim in its title: “Upon the Threatened Extinction of the Art of Letter Writing.” Its prognosis was grim: “In another generation the hand-made letter will be as extinct as hand-made music. It will be used only at one age—the time when life to the young man or the young woman consists merely of a series of long and uninteresting hiatuses between the daily mail deliveries.” Such fears were not entirely unfounded, as seen in the writings of a young girl in 1903: “[I have] a friend who is so foolish that he writes letters. Did you ever heard about anything so ridiculous? As if I care for a good-for-nothing letter.” George Sims complained about this development: “For the purpose of correspondence, they are practically useless. There is so much view, that there is barely room for you to write your name. . . . They are utterly destructive of style, and give absolutely no play to the emotions.” When postcards did convey emotion, they often conveyed too much for the tastes of those raised in the Victorian era. Because postcards traveled without envelopes, they were theoretically open to prying eyes. This sometimes led to serious scandals, as occurred in France when a postal worker intercepted and shared an inappropriate postcard sent to a woman by her local priest. To people who grew up with the social mores of the nineteenth century, this dissolution of privacy and decorum was cause for distress. The art of well-written letters, with their fine-tuned verbal etiquette, seemed doomed for extinction on account of the crass and abbreviated postcard. What was to be done?

Of course, nothing was done. With each passing year, the number of postcards increased, extending their coverage to ever more obscure locales and attractions. “Every pimple on the earth’s skin has been photographed,” wrote James Douglas in 1907, “and wherever the human eye roves or roams it detects the self-conscious air of the reproduced.” In this description of the photographed and commodified world, Douglas perceived the seeds of the postcard craze’s natural decline: “The aspect of novelty has been filched from the visible world. The earth is eye-worn. It is impossible to find anything that has not been frayed to a frazzle by photographers.” Postcard mania eventually subsided. One might cite any number of causes to explain the decline: a loss of novelty, the rise of the personal camera, two World Wars (to say nothing of the financial crash between them). It is unclear if any single development led to the end of the mania. What is clear is that the critics did not win. People may have stopped sending cards out of boredom and fatigue, but they did not stop out of worry for “the experience” of travel, the quality of their train-ride conversations, or the decline of their letter-writing etiquette.

Digital social media can be frightening in its novelty. Developments of the last decade have forced a rapid cultural redefinition of privacy, etiquette, and friendship, and at times the leaps in technology appear to be outstripping our culture’s ability to adapt in a healthy fashion. One might thus forgive the more pessimistic commentators among us for their anxious hang-wringing over social media addiction. The story of the postcard craze, now over a century in the past, should serve to allay our more hysterical fears. At the turn of the twentieth century, ordinary people grappled with the arrival of a new and exciting form of visual communication. Many were addicted; a few were bemused and even disgusted by their compatriots’ passion. As we sail further into the uncharted territory of digital social media, it is important to recognize that our technological obsessions and anxieties—alarming as they may be—are not a complete aberration. Europe emerged from the postcard craze with its social and cognitive functions largely unscathed; the joys of travel, conversation, and a well-written letter did not perish.

One should be careful to not stretch the analogy between postcards and digital social media too far. Indeed they differ in some important ways. Postcards never became tools of official communication; modern social media has turned into an instrument of mass political influence, evolving into something quite different from the image and status-sharing platform as it was originally conceived. A single postcard has one recipient; a single Instagram post may have thousands. Facebook and Twitter allow for instantaneous long-distance communication; postcards, quick and convenient as they may have once appeared, still rely on the slow crawl of the postal system. Postcards offer travelers premade images; modern social media assumes that its users will double as photographers. This final aspect of modern social media allows one to share perspectives that were typically unavailable to the average traveler at the height of the postcard craze: selfies, videos, food photography, pictures taken with monuments rather than photographs of monuments. In a world increasingly saturated with photographs, a picture of the unobstructed Eiffel Tower is hardly cause for a thrill anymore. Modern social media has become more self-centered—alternatively, more intimate and personalized—than postcards could ever allow. But this is a difference of medium, not of generational virtue; armed with a smartphone and Instagram followers, a traveler in 1900 would probably fall into the same habits as any modern traveler. Behind the differences in form lies an uncanny similarity in human nature.

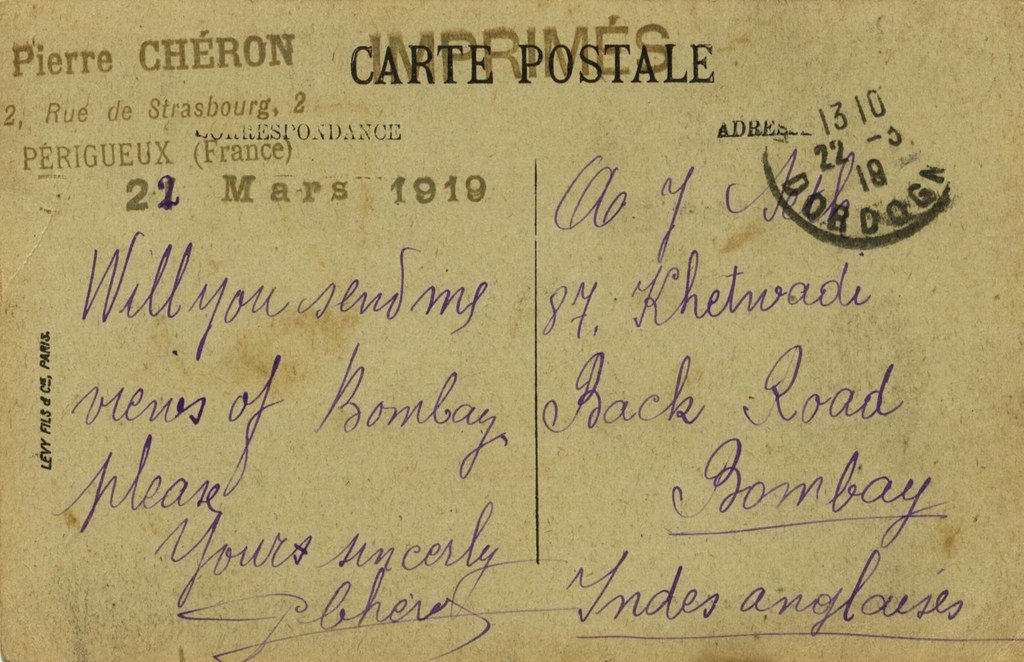

It is sometimes lamented that future historians will shoulder the burden of sifting through the inane and trivial records of our social media lives. Yet few participants in the postcard craze would have expected their cards to hold value to scholars one century after their time. It is often the most ephemeral artifacts—postcards then, social media now—that forge the most relatable links across eras. Postcards are, after all, rather intimate objects: they were not written and addressed to society at large; they were never intended for posterity. As such, their senders were pleased to dwell on the mundane and personal: the weather, travel annoyances, good food, growing babies. Such matters are of little concern for the histories of politics, economics, and ideas, but they offer beautiful glimpses of the past as it was lived and experienced on a daily basis. Some postcards close the gap of a century with just a few words, offering to us a touching snapshot of an ordinary life. Some of them are, with their simplicity and lack of pretension, nothing short of beautiful. George Sims may have dismissed his travel companions as negligent of the beauty surrounding Mt. Rigi, but another mountaintop postcard from 1912, this one from Chamonix, paints as fine and delicate a picture as any landscape painting in just three short sentences: “Ethel and I have not climbed anything quite as steep as this, but we have seen such things as we never saw before. We are right up among the clouds, which are very tame here. They come nosing around just like kittens.”

Lane Baker is postgraduate research fellow working with ephemera at Dumbarton Oaks. Find out more about the Ephemera Collection, and read other stories about the collection.