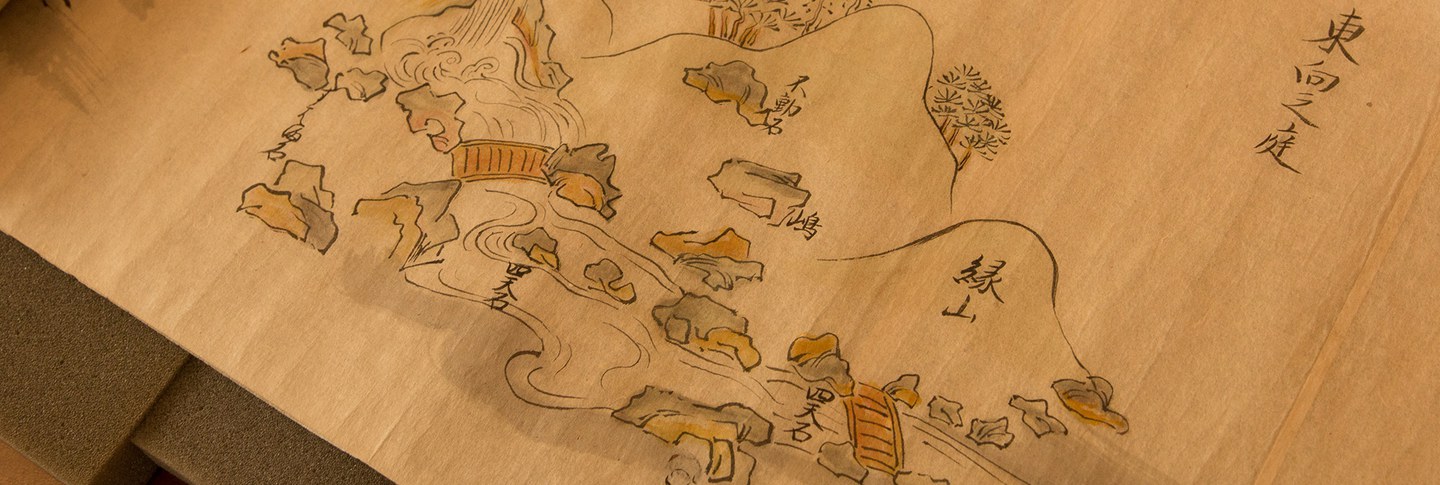

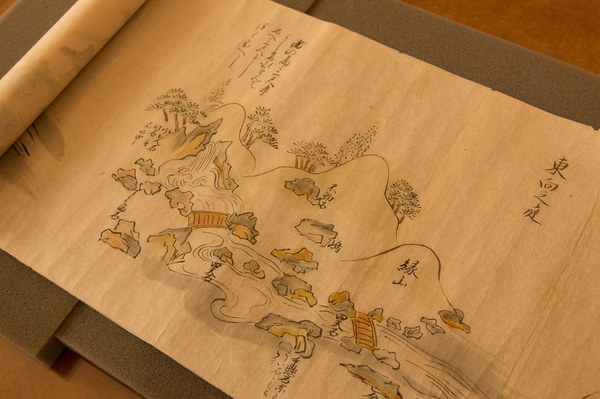

A little more than sixteen feet in length, Kyogoku dono sanseki no zu (The Kyogoku Residence Garden Scroll) is a rare 18th-century Japanese garden design scroll containing thirteen ink paintings of rock gardens. The simple, detached landscapes are painted in subdued shades of green, grey, yellow, and brown, and are heavily annotated with gardening advice and the names of particular structures.

More specifically, the scroll depicts tsukiyama, hill gardens, a style that places carefully chosen stones in a tended environment of sand, water, and unassuming vegetation. The name, which refers to the artificial hills often featured in these gardens, was at one point nearly synonymous with landscape gardening itself in Japan: the title of Tsukiyama teizouden, a 1735 manual on the craft written by the garden designer Kitamura Enkin, takes “tsukiyama” and “garden” to mean roughly the same thing.

In conjunction with Enkin’s text, the Kyogoku scroll sheds light on Japanese garden design culture during the Edo period (1603–1868). Tsukiyama teizouden ranges widely in its subject matter, reworking and synthesizing preexisting manuals while offering information on, among other subjects, the training of pine trees and goldfish husbandry. Its notes on tea gardens reflect a rising taste for the relatively simple style, unsurprising given the increasing number of commoners, like merchants and farmers, who found themselves able to afford personal gardens during the Edo period.

The Kyogoku scroll acts a bit as an instruction manual, offering clear depictions of particular gardens while inserting practical advice that alternates between the precise and the colloquial. The scroll’s image of an “east-facing garden,” for instance, advises that a waterfall should be no taller than sixty centimeters, while text for the “north-facing garden,” abundantly stippled with rocks, reminds the peruser not to overfill the space with stones.

Ultimately, though, the stones make the scene. Carefully selected for their size, shape, and color, and sometimes laboriously transported from distant points of origin, the stones in these illuminated gardens have clearly taken up the bulk of the painter’s care. While the rounded hills and wispy flora present few particular traits, the stones are clearly delineated and present an astonishing variety of types. The importance placed on the choice and arrangement of stones in the garden is exemplified by the practice of naming the stones.

The names given to the stones in the Kyogoku scroll fit the patterns of stone-naming in the broader tradition of Japanese gardening. Beneath, above, and to the sides of the stones, the names explain their function, their position in the landscape, their shape, their resemblance to other objects, or the particular deity whose attributes they embody. In the scroll’s first garden, for instance, the characters announce the “water god rock,” the “morningstar rock,” and the “rock that came down the stream.”

The gardens illustrated in the scroll typify traditional categories of hill garden, for instance, the wide river style, which emphasizes a low waterfall and the use of worn river boulders, and the mountain torrent style, in which stones are carefully placed at the waterfall’s base and throughout the stream to create a rushing, cascading effect.

Despite its age, the Kyogoku scroll has been remarkably well preserved. Other than some minor worming towards its end, the scroll is undamaged, its scenes complete, their muted tones perhaps even gaining from the aged paper of their ground.

Please visit our library pages for information about how to access materials in our Rare Book Collection.