In the middle of the sixteenth century, Melchior Guilandino journeyed east. As he made his way into Palestine, Syria, and Egypt, he hoped to discover new botanical specimens and, perhaps, to disprove, merely by his absence, the rumors back home that had begun to cast his relationship with the eminent anatomist Gabriele Falloppio in a scurrilous light.

Whether it was love or duty that drew Falloppio—already famous for his pioneering studies of the female reproductive system, among other advancements—to pay the price of two hundred scudi for the freedom of Guilandino when the herbalist was captured by pirates off the coast of Africa is difficult to say. Regardless, back in Europe, they were never parted again; their remains lie next to each other in the General’s Cloister of the Basilica of St. Anthony in Padua.

It was after returning to Europe that Guilandino, previously an itinerant Italian herbalist, wrote two botanical treatises, copies of which were recently acquired by Dumbarton Oaks: On Pliny’s Natural History and Botanical Observations.

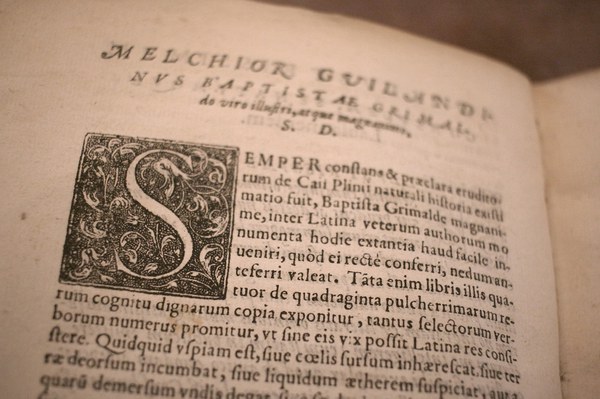

On Pliny’s Natural History analyzes the Roman naturalist’s encyclopedic tome. Its careful examination of chapters and passages from Pliny that focus on medicinal plants and herbs parallels contemporary attempts to revitalize the materia medica. Other scholars, like Guilandino’s occasional rival Pietro Mattioli, had diagnosed the ignorance and disorder typifying sixteenth-century medical practice, especially as it related to botanical cures; many palliative plants mentioned in writers like Pliny and Dioscorides were no longer identifiable, or were sometimes being called by the names of entirely different plants, leading to pharmaceutical concoctions that were placebos at best, and poisonous at worst.

The two volumes also exhibit the influence of Guilandino’s disastrous though ultimately productive trip abroad, which was itself an example of the rising tide of botanical expeditions. On Pliny’s Natural History features a discussion of papyrus and Egyptian flora, which Guilandino had personally encountered, while Botanical Observations collects the observations Guilandino made during his voyage. Taking the form of a series of letters written to fellow naturalists (five of which find Guilandino commenting rather acerbically on the work of Mattioli), Botanical Observations delves richly into botanical nomenclature, providing deep insight into the intricacies of naming that occupied naturalists in the sixteenth century.

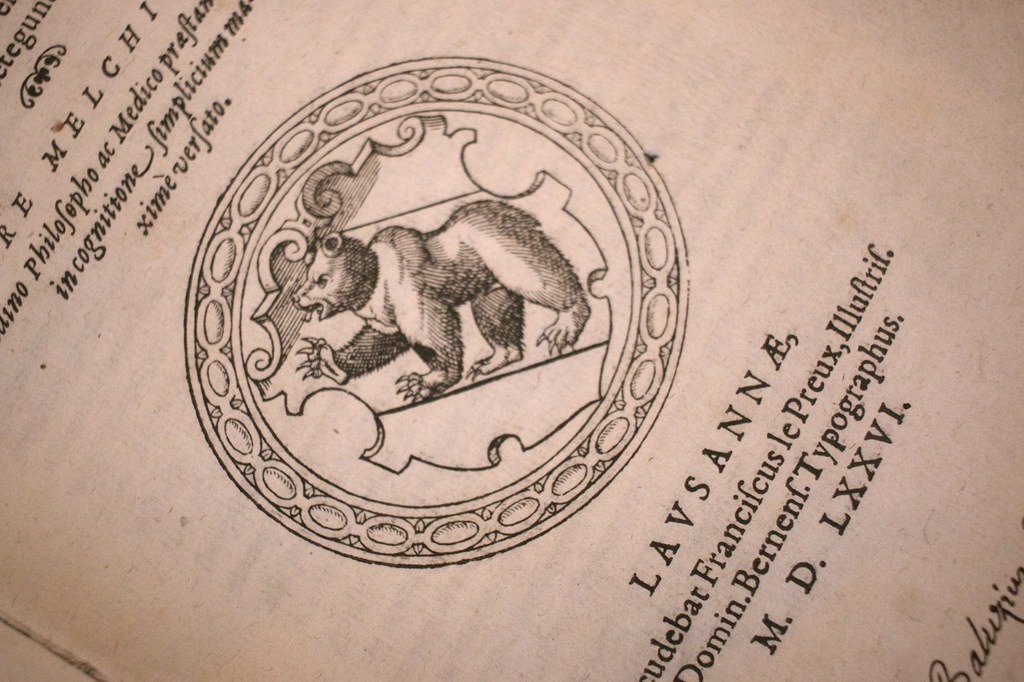

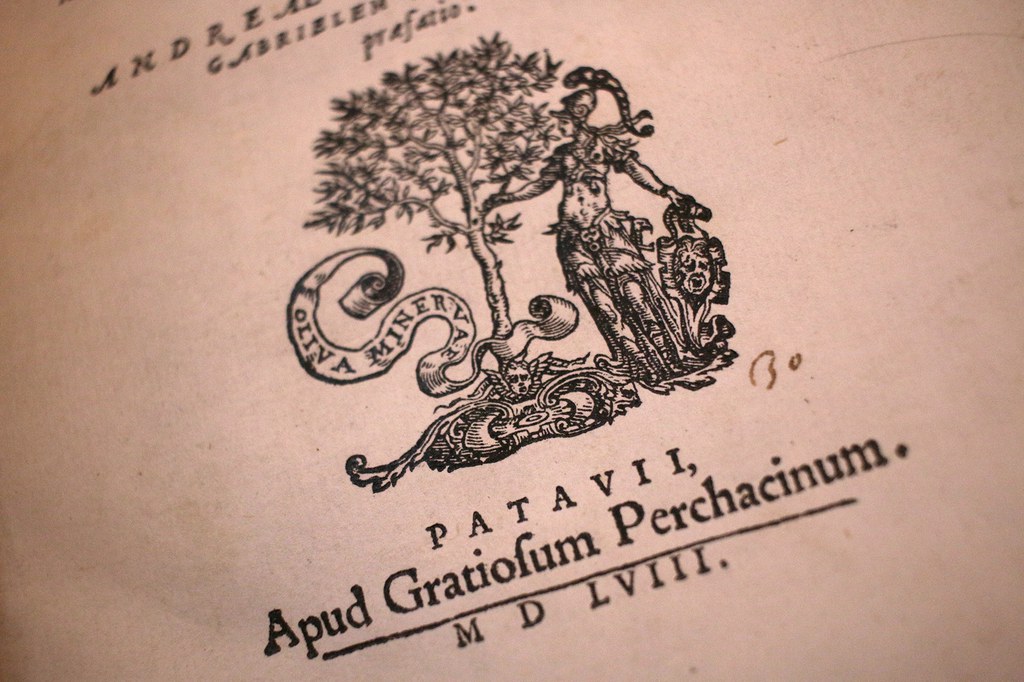

The title pages of the two volumes, which are otherwise unillustrated, feature woodcut devices that, though simple, are striking in their clarity and precision. Above the scrawled signature of the French scholar Étienne Baluz (1630–1718), from whose library Dumbarton Oaks’s copy of On Pliny’s Natural History comes, a bear rampant is set within a simple escutcheon that is itself encircled by an oval motif. The title page of Botanical Observations bears an image of the goddess Athena, elaborately garbed, grasping an olive tree by its branch.

In 1561, four years after the publication of Botanical Observations, Guilandino was appointed prefect of the botanical garden at Padua. Falloppio died the very next year, sending Guilandino into deep despair. Nevertheless, his commitment to his work continued until the end of his own life, for a 1591 catalog of the garden, compiled two years after Guilandino’s death, lists nearly twelve hundred plants in its living collection.

In addition to his celebrated reign over the botanical garden of Padua, Guilandino was appointed to a lectureship at the University of Padua—a remarkable rise for the herbalist who had grown up Melchior Wieland in poor circumstances in Königsberg.