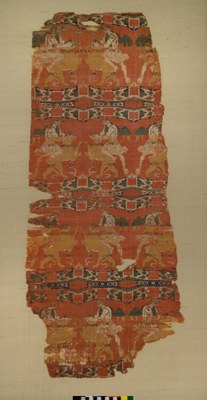

“Hero and Lion” Silk

| Accession number | BZ.1934.1 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Constantinople? Egypt? Syria?,

7th–9th c.

|

| Measurements |

H. 94.2 × W. 38.4 cm (37 1/16 × 15 1/8 in.) |

| Technique and Material |

Weft-faced compound twill (samite) in polychrome silk |

| Acquisition history |

Acquired by Giorgio Sangiorgi from the Cathedral of Chur, Switzerland, between 1924 (according to November 12, 1949, letter from Giorgio Sangiorgi) and 1927 (according to November 25, 1949, letter of Christian Caminada, Bishop of Chur); Collection of Giorgio Sangiorgi (1886–1960), Rome, to 1934; Purchase from the Galleria Sangiorgi, Rome, September 1934, by Robert Woods and Mildred Barnes Bliss; Gift of Robert Woods and Mildred Barnes Bliss to Harvard University, Dumbarton Oaks Library and Collection, 1940. |

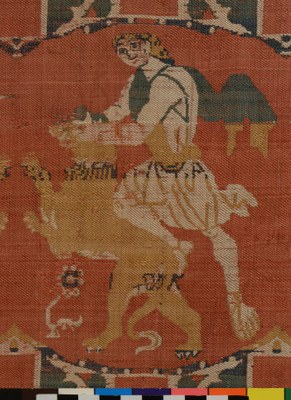

This textile depicts a repeated motif of a muscled man subduing a lion. The wide-open, staring eyes of the lion-fighter may signal a moment of keen intent or divine possession.Wide-open eyes as a sign of divine madness or possession in late antiquity is discussed in V. Rondot, “Le dieu à la bipenne, c’est Lycurgue,” Revue d’Egyptologie 52 (2001): 219–36 and plates XXIX–XXV; and idem, “La folie de Lycurgue de l’Arabie à l’Égypte anciennes,” in D’un orient l’autre: Actes des troisième journées de l’Orient, Bourdeaux, 2–4 Octobre 2002, ed. J.-L. Bacqué-Grammont, A. Pino, and S. Khoury (Paris, 2005), 44. Certainly, the gaze of divine possession was known earlier in Greco-Roman Egypt: see the mosaic of the female bust from Thmuis of the second to first century BCE (Alexandria, Graeco-Roman Museum, inv. 21739; K. M. D. Dunbabin, Mosaics of the Greek and Roman World [Cambridge, 1999], fig. 25); the intent stares of the erotes in the third-century BCE mosaic of a stag hunt from Shatby, Alexandria, are quite similar (Alexandria, Graeco-Roman Museum, inv. 21643; Dunbabin, Mosaics, figs. 22–23). He wears a one-shouldered short tunic and a cape that flaps out behind him, and grabs the lion from behind his head as the beast rears up on its hind legs. The pair of figures, woven in tan and white with touches of green and blue in the cape of the man, and on the neck, haunches, and claws of the lion, repeats in rows on a red ground, separated by a white arcuated border containing plants sprouting from red squares. Four rows remain, with at least traces of three figural pairs per row. Originally, there were probably at least four pairs, as the even number of pairs would have produced a symmetrical design in harmony with the symmetrical composition.

The lack of an inscription thwarts secure identification of the human figure. He could conceivably be the biblical Samson, who ripped apart a lion with his bare hands. The motif might instead portray Heracles wrestling the Nemean lion, echoing classical textual and artistic references to the hero grappling with the beast.For known descriptions of this episode, see http://www.theoi.com/Ther/LeonNemeios.html. The longest, most detailed description is Theocritus, Idylls 25.141–281 (Hellenistic, third century BCE). See also Diodorus Siculus, Library of History 4.11.3 (first century BCE), and the late antique (fifth-century) account of Nonnos, Dionysiaca 25.176, trans. W. H. D. Rouse (Cambridge, MA, 1940), 262–65: “[Heracles] threw his arm from one side and circled the lion’s neck entangled in mighty grip, and so without weapon brought death, in that spot where the breath passes through the gullet of the life sufficing throat.”

Lions are also associated with the biblical figures of Daniel and David, as well as Roman gladiators. Animal-tamer imagery and scenes of hunters are common on textiles, and this motif certainly fits in those genres.H. Pierce and R. Tyler, “Elephant-Tamer Silk, VIIIth Century,” DOP 2 (1941): 19–26. The fifth-century BCE Olympic wrestler Poulydamas, for instance, killed a lion with his bare hands; R. L. Fox, “Ancient Hunting: From Homer to Polybios,” in Human Landscapes in Classical Antiquity: Environment and Culture, ed. G. Shipley and J. Salman (London, 1996), 136. Whatever the figure’s identity, the scene celebrates extraordinary strength and courage. The lack of an inscription may be a deliberate strategy to leave the identification of the figure open to various interpretations.

The lion in the scene may be at least as important as the heroic figure. If we identify them as Heracles and the Nemean lion, the image could refer to their constellations.The constellation Leo was associated with the Nemean lion: see Hyginus, Astronomica 2.24, in The Myths of Hyginus, ed. and trans. M. Grant (Lawrence, KS, 1960), online at http://www.theoi.com/Text/HyginusAstronomica2.html#24. In his constellation, Heracles kneels, alone and, notably, wrapped in the lion’s skin. See Hyginus, Astronomica, 2.6, in Eratosthenes and Hyginus, Constellation Myths, with Aratus’s Phaenomena, trans. R. Hard (Oxford, 2015), 26–31 (on Hercules the Kneeler) and 69–72 (on Leo). If so, then the related five-color silks of the Dioscuri twins, Castor and Pollux, may have astronomical and astrological associations as well, given the twins’ connection to Gemini.See, e.g., New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 37.53.2, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/449158. Both of these popular themes may be associated with the five-color scheme used in contemporaneous (as well as earlier and later) Chinese silks, which sometimes employed red, sometimes blue backgrounds which had astral associations.F. Zhao, “Woven Color in China/The Five Colors in Chinese Culture and Polychrome Woven Textiles,” in Textiles and Settlement: From Plains Space to Cyber Space; Proceedings of the 12th Biennial Symposium of the Textile Society of America, October 6–9, 2010, Lincoln, Nebraska (2010), http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1063&context=tsaconf. In the silks produced during the Han dynasty (first–fourth century) and the Tang dynasty (seventh–eighth century), the typical color scheme resembled that used for the Dumbarton Oaks silk (blue, red, yellow, green and white), and which referred also to constellations.Ibid., 4. It seems possible that this distinctive color scheme could have retained exotic cosmic associations and auspicious connotations in its Sassanian, Roman, and late antique appropriations.

Many of the late antique group of red background, five-color silks like this textile exhibit abrupt color shifts (e.g., the shift in the mantle from green to gold, the green at the top of the lion’s head, and the blue part of the mane).In its original, unfaded, even more vibrant appearance, the color bands (especially the blue) would have been even more noticeable. The dark blue, for instance, could have been carried through invisibly between the textile surfaces until it would “pop” out in the center of the bright, white flower. This type of color banding appears to enter the Greco-Roman repertory with Central Asian silks. Although quite different in style, iconography, and composition from the Central Asian “lion-strangler silks” (such as the Shroud of St. Victor at Sens Cathedral), in which the hero stands between two lions and grips their throats, their subjects and themes may be related.

The ornamental vocabulary of the Dumbarton Oaks silk, however, is decidedly Greco-Roman.The arcing band framed by pearls with a vine running along its center can be seen in Pompeii VI, 8, 23, the House of the Small Fountain (late first century CE), where it appears as part of the design separating the gable from the niche and wall below: Dunbabin, Mosaics, 242, fig. 256 and plate 36. The fluid, curvilinear shapes of the anatomy, drapery, and the man’s hair are characteristic of Byzantine style.Compare to the Vatican Annunciation, which does not have obvious color banding.

The function of this cloth remains unclear. Carolyn Connor has proposed that it was once part of a garment;C. L. Connor, Women of Byzantium (New Haven, 2004), 144. as, for example, in a fourth-century text of Bishop Asterius of Amaseia (northern Turkey), in which he complained about the sacrilege of people wearing clothing decorated with holy figures.C. Mango, Art of the Byzantine Empire 312–1453: Sources and Documents (Toronto, 1972), 50–51. There is little pictorial or archaeological evidence, however, to suggest that this design must have been used on clothing.J. Ball, Byzantine Dress: Representations of Secular Dress in Eighth- to Twelfth-Century Painting (New York, 2005), appendix of extant textile fragments likely to have been garments. Mythological subjects are often found on textile furnishings. Moreover, evidence from wills and dowries as well as monastic and church inventories demonstrate that clothing may have been reused as furnishings in liturgical and domestic settings.

The date and place of production of this piece and the nearly twenty silks with this same motif are uncertain.For a complete list of the versions of this textile, see M. Martiniani-Reber, Lyons, Musée historiques des Tissus: Soieries sassanides, coptes et byzantines, Ve–XIe siècles (Paris, 1986), 99–100. The so-called Mantle of St. Alexander, in Ottobeuren, is the largest fragment of a “Samson silk,” dated to the eighth to ninth century in S. Muller-Christensen, Ottobeuren 764–1964 (1964), 39–44. Other examples from Martiniani-Reber’s list include: Paris, Musée de Cluny, Cl. 3055; Vatican, inv. T103: W. F. Volbach, I tessuti del Museo Sacro Vaticano (Vatican City, 1942), 38–39; Sens Cathedral, B135/1; Lyon, Musée Historique des Tissus, inv. 875.III.1, originally found in the cathedral of Coire, Switzerland. A. C. Weibel notes that a textile of this same design “was used as part of the binding of a ninth-century Gregorian Sacramentary”; A. C. Weibel, Two Thousand Years of Textiles: The Figured Textiles of Europe and the Near East (New York, 1952), 89, citing G. Gerola, Il Sacramentario della Chiesa di Trento (Milan, 1921), 221. The attribution of the textile has been debated since the turn of the century.“Notes on an Early Silk Weave,” The Bulletin of the Needle and Bobbin Club 27 (1943): 40–47; O. von Falke, Kunstgeschichte der Seidenweberei (Berlin, 1913), 1:54. Both Constantinople and Alexandria have been suggested because of their flourishing textile industries and trade in late antiquity. However, there is no clear evidence to locate the textile in either city. Adèle Coulin Weibel attributed the piece to Syria, which also had a flourishing textile industry. She noted the large number of textiles that came from Syria-Palestine with relics and made their way into European treasuries.Weibel, Two Thousand Years of Textiles, 36–37. Thompson discussed the possibility that it could be from Antinoopolis without settling on a firm attribution.D. Thompson, “Catalogue of Textiles in the Dumbarton Oaks Collection” (unpublished catalogue, Washington, DC, 1976), no. 163. When it was shown in the 2012 Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition, the curators labeled it as “Eastern Mediterranean” and used the date assigned by Dumbarton Oaks, late sixth to seventh century.

—Jennifer L. Ball and Thelma K. Thomas, May 2019

Notes

| Accession number | BZ.1934.1 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Constantinople? Egypt? Syria?,

7th–9th c.

|

| Measurements |

H. 94.2 × W. 38.4 cm (37 1/16 × 15 1/8 in.) |

| Technique and Material |

Weft-faced compound twill (samite) in polychrome silk |

| Acquisition history |

Acquired by Giorgio Sangiorgi from the Cathedral of Chur, Switzerland, between 1924 (according to November 12, 1949, letter from Giorgio Sangiorgi) and 1927 (according to November 25, 1949, letter of Christian Caminada, Bishop of Chur); Collection of Giorgio Sangiorgi (1886–1960), Rome, to 1934; Purchase from the Galleria Sangiorgi, Rome, September 1934, by Robert Woods and Mildred Barnes Bliss; Gift of Robert Woods and Mildred Barnes Bliss to Harvard University, Dumbarton Oaks Library and Collection, 1940. |

Paris, Musée des arts décoratifs, Exposition internationale d'art byzantin, May 28–July 9, 1931.

Worcester, MA, Worcester Art Museum, Art of the Dark Ages, February 20–March 21, 1937.

Brooklyn, NY, Brooklyn Museum, Exhibition of the History of Costume, March 14–May 19, 1940.

New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition, 7th–9th Century, March 14–July 8, 2012.

| Accession number | BZ.1934.1 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Constantinople? Egypt? Syria?,

7th–9th c.

|

| Measurements |

H. 94.2 × W. 38.4 cm (37 1/16 × 15 1/8 in.) |

| Technique and Material |

Weft-faced compound twill (samite) in polychrome silk |

| Acquisition history |

Acquired by Giorgio Sangiorgi from the Cathedral of Chur, Switzerland, between 1924 (according to November 12, 1949, letter from Giorgio Sangiorgi) and 1927 (according to November 25, 1949, letter of Christian Caminada, Bishop of Chur); Collection of Giorgio Sangiorgi (1886–1960), Rome, to 1934; Purchase from the Galleria Sangiorgi, Rome, September 1934, by Robert Woods and Mildred Barnes Bliss; Gift of Robert Woods and Mildred Barnes Bliss to Harvard University, Dumbarton Oaks Library and Collection, 1940. |

J. H. von Hefner-Alteneck, Trachten des christlichen Mittelalters: Nach gleichzeitigen Kunstdenkmalen (Mannheim, Frankfurt, Darmstadt, 1840–54), 1: plate 8.

J. Burckhardt, “Domkirche von Chur,” Mitteilungen der antiquarischen Gesellschaft in Zürich 11, no. 7 (1857): 161, plate 14.

C. de Linas, Revue des sociétés savantes des départements 2 (1857): 63.

J. H. von Hefner-Alteneck and C. Becker, Trachten, Kunstwerke und Geräthschaften vom frühen Mittelalter bis Ende des achtzehnten Jahrhunderts nach gleichzeitigen Originalen. 2nd ed. (Frankfurt am Main, 1879–89), 1: plate 5.

E. Molinier, Le trésor de la cathédrale de Coire (Paris, 1895), plate 22.

G. Migeon, “Essai de classement des tissus de soie décorés sassanides et byzantins,” Gazette des Beaux Arts 40 (1908): 485.

G. Migeon, Les arts du tissu (Paris, 1909, repr. 1929), 30, plate on p. 29.

O. von Falke, Kunstgeschichte der Seidenweberei (Berlin, 1913), 1:54.

W. F. Volbach, Spätantike und frühmittelalterliche Stoffe (Mainz, 1932), 47, no. 61.

O. von Falke, “Der Simsonstoff der Sammlung Sangiorgi,” Pantheon 9 (1932): 63.

F. Morris, “Catalogue of Textile Fabrics, The Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection” (unpublished catalogue, Washington, DC, 1940), 71–97.

W. F. Volbach, I tessuti del Museo Sacro Vaticano (Vatican City, 1942), 39, fig. 15.

“Notes on an Early Silk Weave.” The Bulletin of the Needle and Bobbin Club 27 (1943): 40–47.

Dumbarton Oaks, Handbook of the Collection (Washington, DC, 1946), 120–21, no. 228, fig. on p. 131.

A. C. Weibel, Two Thousand Years of Textiles: The Figured Textiles of Europe and the Near East (New York, 1952), no. 44.

Dumbarton Oaks, The Dumbarton Oaks Collection, Harvard University: Handbook (Washington, DC, 1955), 156–57, no. 308, fig. on p. 164.

K. Wessel, Koptische Kunst: Die Spätantike in Ägypten (Recklinghausen, 1963), 219–20, fig. 129.

Dumbarton Oaks, Handbook of the Byzantine Collection (Washington, DC, 1967), 110, no. 371.

D. Thompson, “Catalogue of Textiles in the Dumbarton Oaks Collection” (unpublished catalogue, Washington, DC, 1976), no. 163.

Byzance: L’art byzantin dans les collections publiques françaises (Paris, 1992), 199.

C. L. Connor, Women of Byzantium (New Haven, CT, 2004), 143–44, color plate 8.

N. Metallinos, ed., Byzantium: The Guardian of Hellenism (Montreal, 2004), 118, fig. 7 (detail of hero and lion).

G. Bühl, ed., Dumbarton Oaks: The Collections (Washington, DC, 2008), 130, plate on p. 131.

H. C. Evans and B. Ratliff, eds. Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition, 7th–9th Century (New York, 2012), 122, 153–154, no. 102A.

J. Galliker, “Application of Computer Vision to Analysis of Historic Silk Textiles,” in Drawing the Threads Together: Textiles and Footwear of the 1st Millennium AD from Egypt, ed. A. De Moor, C. Fluck, and P. Linscheid (Tielt, 2013), figs. 5 and 11.

| Accession number | BZ.1934.1 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Constantinople? Egypt? Syria?,

7th–9th c.

|

| Measurements |

H. 94.2 × W. 38.4 cm (37 1/16 × 15 1/8 in.) |

| Technique and Material |

Weft-faced compound twill (samite) in polychrome silk |

| Acquisition history |

Acquired by Giorgio Sangiorgi from the Cathedral of Chur, Switzerland, between 1924 (according to November 12, 1949, letter from Giorgio Sangiorgi) and 1927 (according to November 25, 1949, letter of Christian Caminada, Bishop of Chur); Collection of Giorgio Sangiorgi (1886–1960), Rome, to 1934; Purchase from the Galleria Sangiorgi, Rome, September 1934, by Robert Woods and Mildred Barnes Bliss; Gift of Robert Woods and Mildred Barnes Bliss to Harvard University, Dumbarton Oaks Library and Collection, 1940. |