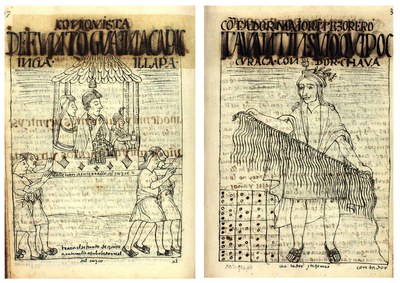

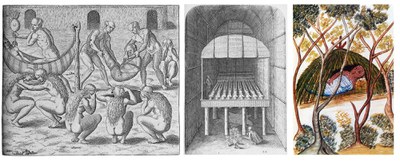

The left drawing shows the mummy of Huayna Cápac, leader of the Inca Empire, being carried from Quito to Cuzco. The monarch succumbed to an unknown disease, likely smallpox, sometime between 1524 and 1528. Throughout the long journey, communities rendered homage to the deceased monarch, unwittingly spreading the germs that had vanquished their leader.

The European pathogen that vanquished Huayna Cápac preceded the arrival of the Spanish in 1532, transmitted by contact between neighboring communities. The monarch likely fell ill in Quito, just as he was concluding a war that expanded his empire up to what is now northern Ecuador. Aware of his impending death, he named his oldest son Ninan Cuyuchi as his successor. By the time messengers arrived to Tomebamba (modern-day Cuenca, Ecuador) to inform Ninan Cuyuchi of his enthronement, he had already perished from the disease that had killed his father. The empty throne led to a bloody civil war between Atahualpa and Huáscar, the two other aspirants to Inca leadership. When the Spanish arrived in the Andes in 1532, they found an empire composed of communities still recovering from the Inca wars of expansion, engaged in a fierce civil war, and confronting an unstopping, devastating epidemic that was killing Andeans by the hundreds of thousands. Similar scenarios played out in the rest of the continent, as epidemics leaped ahead of the Spanish, devastating communities and facilitating the swift invasion of the Europeans.

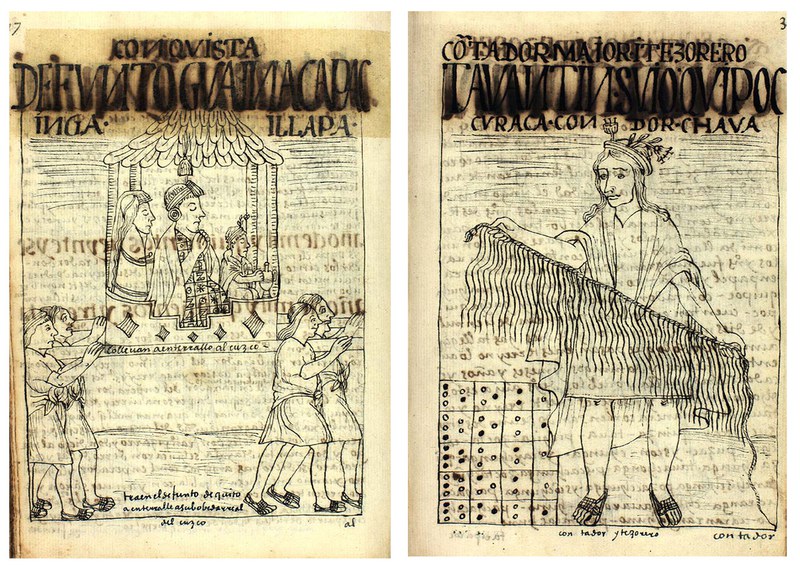

By 1620, the Andean Native population had declined by approximately 90 percent due to epidemics, war, and colonial exploitation. Among the many victims were a class of scholars that specialized in knotting and reading khipus, the knots-based writing artifacts with which Incas recorded knowledge. The right drawing illustrates one such specialist, or khipukamayuq. The extinction of these scholars led to a loss of Andean recorded memory, dooming later generations to understand the Andean past through the myopic lenses of Spanish sources.

Image Source

- Felipe Guamán Poma de Ayala. Nueva corónica y buen gobierno. 1615. Royal Library of Denmark, Copenhagen, Gl. kgl. S. 2232, fols. 379 and 362. Courtesy of the Royal Library of Denmark, Copenhagen.

Further Reading

- Cook, Noble David. Born to Die: Disease and New World Conquest, 1492–1650. New Approaches to the Americas. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Crosby, Alfred W. The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of 1492. Contributions in American Studies 2. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1972.