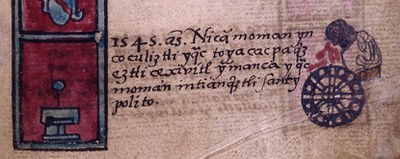

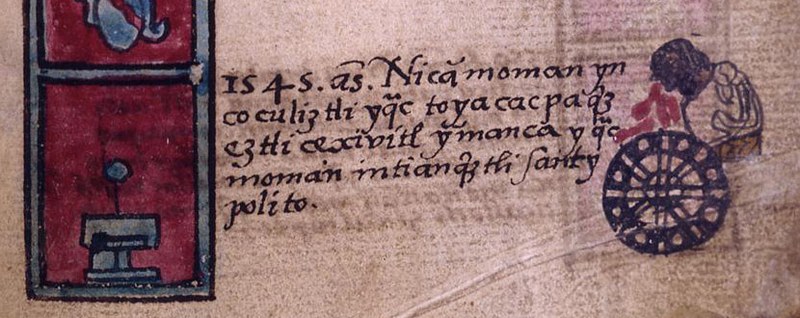

This visual calendar represents the year 1545 with a man experiencing profuse nose bleeding. The Nahuatl text reads, “Here the plague [cocoliztli] extended. It was when blood came out from our noses. It lasted a year” (Dibble 1963:65).

Among countless epidemic outbreaks that shattered the Valley of Mexico, the cocoliztli outbreak of 1545 stands out because of its catastrophic mortality rate. Patients experienced high fevers and profuse bleeding, leading to a swift death. The pathogen, likely a subspecies of Salmonella enterica, devastated a population already weakened by decades of exposure to foreign germs, colonial exploitation, and warfare. The peak of the epidemic lasted six months, and it was accompanied by severe drought. The mortality rate was colossal: in Tlaxcala alone, up to one thousand people died daily; and in Tlatelolco, Bernardino de Sahagún claimed to have attended ten thousand patients and fell ill himself. Toribio de Benavente “Motolinia” reports a death rate among the Natives of 60 to 90 percent. It is now estimated that the outbreak killed between five and fifteen million people—a collapse of the Indigenous population of approximately 80 percent.

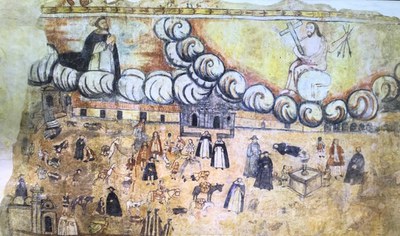

Colonists struggled to understand why the Natives were so prone to illness. Some blamed Native bathing practices, others accused the local climate, and some even attributed it to Indigenous psychology. Divine intervention was frequently listed as a cause of disease. A sympathetic friar attributed the epidemics to God’s mercy, as it delivered the Natives from the evils suffered under colonial control. The Jesuit José de Anchieta believed the plagues to be God’s punishment against the idolatrous Natives, and a call to God for those who were already Christianized. Others saw in the extermination divine mandate and opportunity: the friar Gerónimo de Mendieta thought the plagues a message from God: “God is telling us: ‘You are hastening to exterminate this race. I shall help you to wipe them out more quickly’”; while John Winthrop, governor of Massachusetts, wrote that “for the Natives, they are nearly all dead of smallpox, so has the Lord cleared our title to what we possess” (Sandine 2015:158).

Image Source

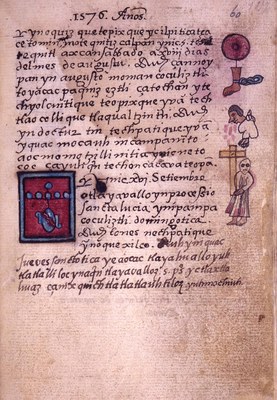

- London, British Museum, Aubin Codex, 1576, fol. 47v. Courtesy of the British Museum, © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Further Reading

- Acuna-Soto, Rodolfo, et al. “Megasequía y mega-muerte en México en el siglo XVI.” Revista Biomédica 13, no. 4 (2002): 289–92.

- Cook, Noble David. Born to Die: Disease and New World Conquest, 1492–1650. New Approaches to the Americas. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Dibble, Charles E. Historia de la nación mexicana: Reproducción a todo color del Códice de 1576 (Códice Aubin). Colección “Chimalistac” de libros y documentos acerca de la Nueva España 16. Madrid: J. Porrúa Turanzas, 1963.

- Guevara Flores, Sandra Elena. “A través de sus ojos: Médicos indígenas y el cocoliztli de 1545 en la Nueva España.” eHumanista 39 (2018): 36–52.

- Sandine, Al. “Micro-Invaders.” In Deadly Baggage: What Cortes Brought to Mexico and How It Destroyed the Aztec Civilization, 154–65. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2015.

- Vågene, Åshild J., et al. “Salmonella enterica Genomes from Victims of a Major Sixteenth-Century Epidemic in Mexico.” Nature Ecology & Evolution 2 (2018): 520–28.