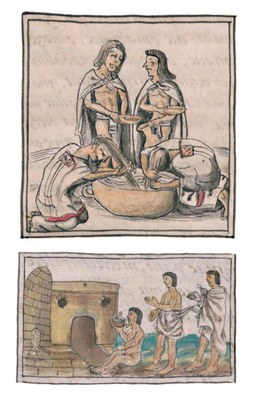

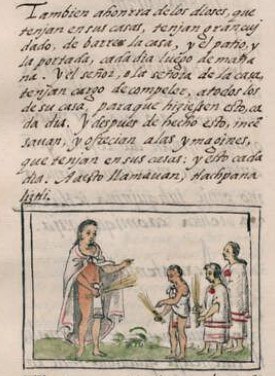

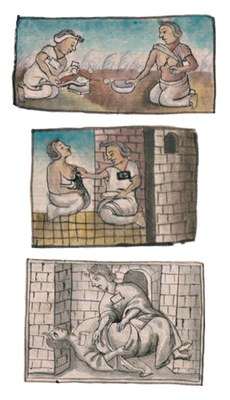

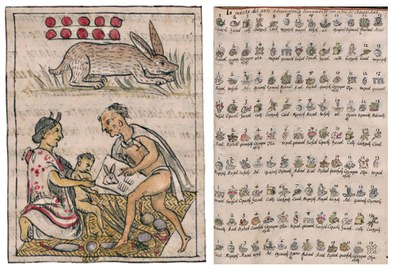

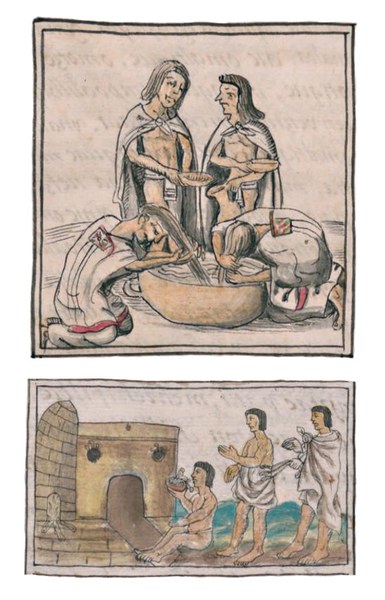

In the top image, two Nahua women wash their hair after twenty days of not bathing, a penitence to honor the ritual sacrifice of a sacralized captive. In the bottom image, a sitting patient drinks herbal medicine before entering a sweat bath, or temazcalli, as part of a treatment to cure bruises.

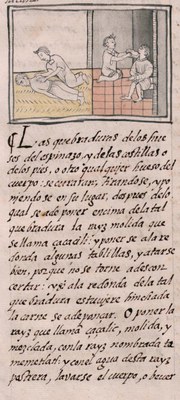

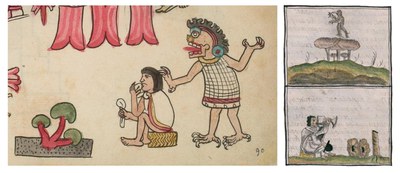

These images are testaments to the scrupulous cleaning habits of the people of the Valley of Mexico, and demonstrations of the inextricable connections among hygiene, health, and ritual in the Nahua world. Nahuas considered hygiene essential for physical and moral integrity. From an early age, children were educated on the importance of washing their bodies and clothes, and new couples were advised on the value of cleanliness for a successful relationship. Handwashing was of utmost importance, and soaps made of the copalxocotl herb and the xiuhamolli root were used abundantly, as were toothpastes, deodorants, and breath fresheners. Nahuas bathed on a regular basis to cleanse body and spirit, and used detoxifying sweat baths (temazcalli) to treat ailments ranging from spider bites to broken bones. The advice of noble parents to their children in the Florentine Codex highlights the importance of cleaning rituals: “get in the water, clean yourself, bathe, but only when necessary” and “when you eat, wash your hands, your face, your mouth . . . after the meal clean and sweep the place” (Díaz Cíntora 1995:60, 114).

European colonizers regarded the cleaning habits of Mesoamericans with suspicion. Public bathhouses were in rapid decline in sixteenth-century Europe as they were suspected hotbeds of disease and promiscuity. The Arab occupation of the Iberian Peninsula also led many Spaniards to associate Moorish bathing habits with paganism. Witnessing the epidemics that ravaged Mesoamerica in the sixteenth century, some Spaniards attributed the widespread insalubrity to the Nahuas’ rigorous cleaning habits.

Image Source

- Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, MS Mediceo Palatino 220 (Florentine Codex), book 2, fol. 26v (1:80v), and book 10, fol. 113v (3:115v). Courtesy of the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana.

Further Reading

- Díaz Cíntora, Salvador. Huehuetlatolli: Libro sexto del Códice Florentino. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1995.

- Dufendach, Rebecca. “Nahua and Spanish Concepts of Health and Disease in Colonial Mexico, 1519–1615.” PhD diss., University of California, Los Angeles, 2017.

- Ortiz de Montellano, Bernard R. “Medicina y salud en Mesoamérica.” Arqueología Mexicana 74 (2005): 32–47.