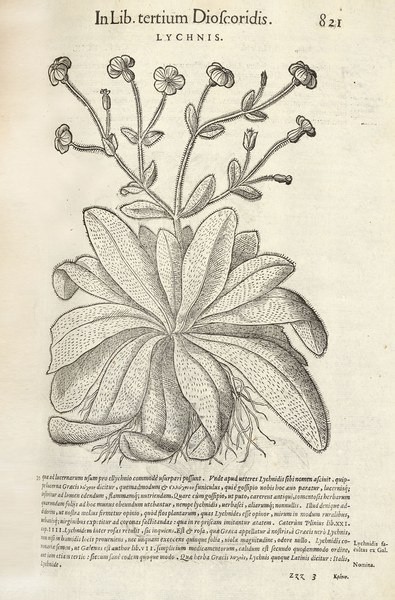

The Dumbarton Oaks rare book collection holds three of the more than 100 surviving woodblocks in the editions of the Commentarii in sex libros Pedacii Dioscoridis de medica materia by Pietro Andrea Mattioli (1501–1577) that were published in 1562 and 1565. The Dumbarton Oaks woodblocks depict the plants Imperatoria, Galega sive ruta, and Lychnis.

Mattioli was a Siena-born physician who served in the court of Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I and his successor, Maximilian II. The study of plants has been associated from the earliest times with medicine and pharmacopoeia, a type of book with directions for identifying compound medicines. Mattioli’s book is an herbal: an early printed book of images and descriptions of plants and their properties, with an emphasis on their medicinal qualities. Comprising between 500 and 1000 woodcuts, Mattioli’s herbal was a very popular commentary on Dioscorides’ foundational botanical text, De materia medica.

Created between 1530 and 1565, the Mattioli woodblocks were drafted by the Italian painter Giorgio Liberale (1527–ca. 1579) and the German woodcutter Wolfgang Meyerpeck (ca. 1505–1578) and cut by no fewer than five woodcutters. Created for a practical purpose—to print book illustrations—the surviving woodblocks have found their way to special collections as valuable objects in their own right. Today they are admired for their craftsmanship and beauty, as well as for their significant contribution to sixteenth-century botanical illustration, when plant representations grew in number and became more detailed and naturalistic (fig. 7).

Early modern printing technology made reproducing text and image much faster and easier, and allowed for a much larger number of images. Mattioli’s herbals were sold throughout Europe, and new woodblocks depicting faithful or partially altered designs from the Mattioli woodcuts were created to illustrate other contemporary herbals, since copyright was still in its infancy. The copying of the Mattioli woodcuts also extended to painted works, contrary to the common belief that paintings or drawings were the visual sources that woodcuts sought to reproduce. For example, the manuscript by the Italian painter Giovanna Garzoni, featured in this exhibition, includes a watercolor of the Imperatoria. The image is recognizably an enlarged color copy of Mattioli’s woodcut (figs. 8–9).

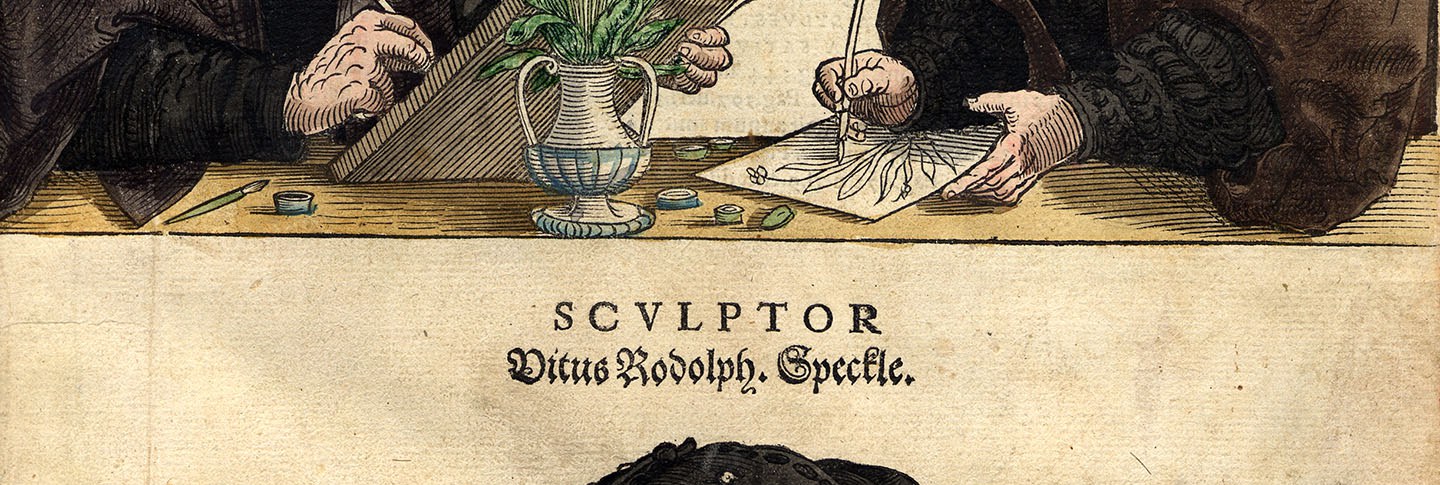

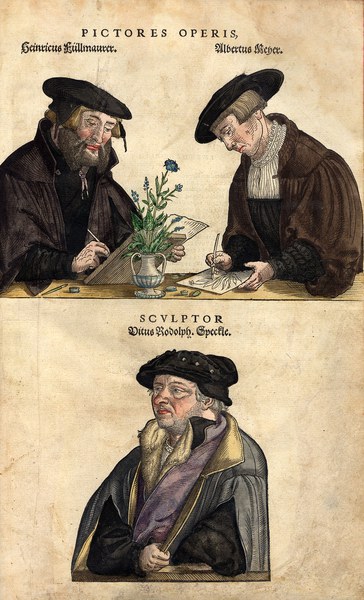

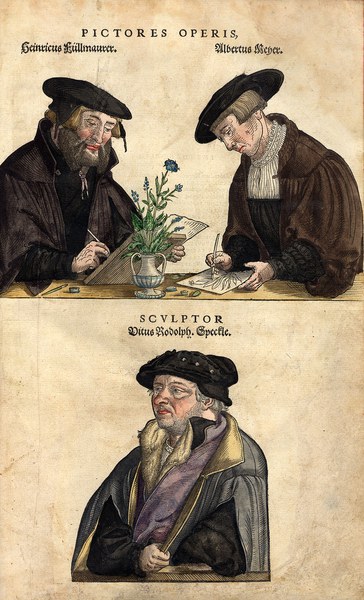

Fig. 7. Leonard Fuchs, De historia stirpium commentarii insignes (Basel, 1542), Dumbarton Oaks Rare Book Collection.

Fig. 8. Mattioli woodcut of Imperatoria, Dumbarton Oaks Rare Book Collection.

Fig. 9. Imperatoria, Giovanna Garzoni, Piante Varie (ca. 1631), Dumbarton Oaks Rare Book Collection.

Woodcut, Engraving, and Etching

These are the three major techniques for printing images in the early modern period. Woodcut is a type of relief printing, whereas engraving and etching are intaglio printing methods. To make a relief, a woodcutter cuts away the unwanted areas on a thin block of wood. What remains uncut—the linework—is inked and printed by using a hand press. In contrast, to make an intaglio a printmaker engraves lines into a metal (usually copper) plate with a burin or etches an image by immersing a prepared and drawn plate into an acid bath. When printing, ink is rubbed into the grooves and the image is printed with a high-pressure rolling press.

As the lead types that were used to set the text for books are also a kind of relief printing tool, woodblocks could be printed at the same time as the types by using the same hand press. Woodcuts therefore offered greater flexibility for integrating text and illustration. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, despite the growing preference for copperplate engravings, woodcuts remained an important image-making technique for printed herbals because they allowed the inclusion of copious illustrations without exceedingly high production costs.

Making a Woodblock

The process of making a woodblock for relief printing appears simple, but it requires a high level of skill and knowledge. All craftsmen work in their own unique ways, but early modern woodcutting shared commonalities across Europe. In general, the creation of a woodblock required a draftsman and a cutter, although sometimes one person fulfilled both roles. The draftsman drew the design directly or transferred an image from a printed or sketched source onto a planed woodblock. Sometimes a piece of paper with the design would be pasted onto a block instead. Once the design was on the woodblock, the cutter could proceed with the cutting.

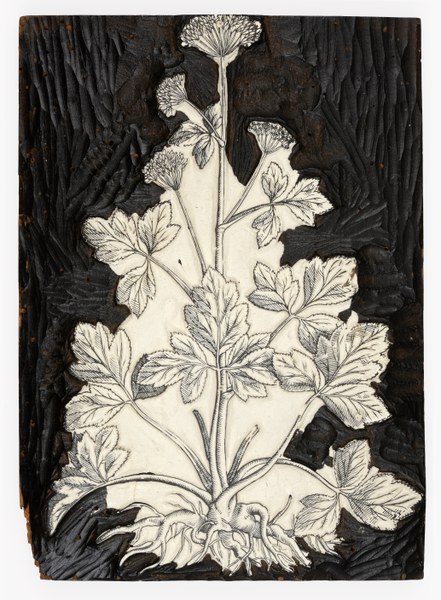

Woodcutting requires a firm grasp of the material qualities of wood. Most often, planed woodblocks were made out of fruitwood trunks that were sawn lengthways. The Mattioli woodblocks have been identified as pearwood. Pearwood (and most kinds of fruitwood) is a hardwood with an even and smooth grain. The wood density is soft enough to enable the cutter to work with relative ease, but hard enough to endure going under a press thousands of times without breaking. It has a light pinkish-brown or yellowish-white color that allows the cutter to see the drawn lines and remove the unwanted areas. Despite the occasional knots on a block that a woodcutter would need to work around, pearwood’s qualities and wide availability made it suitable for making woodblocks.

The major skill of a woodcutter is to master using a simple tool to remove the unwanted areas on a woodblock. The woodcutting knife was usually a piece of steel with a pointed tip, with the bevel of the blade set on the left side, and a wooden handle for better gripping. In principle, the depth of the removed areas is shallower in the more detailed parts of a design and deeper where a larger area is empty. When a cutter did not clear enough wood in the unwanted space, the wetted paper would sag into the void during printing and result in a messy print by picking up ink from the shallow background.

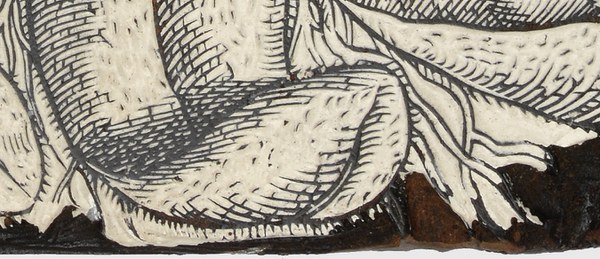

Additionally, a cutter needed to calculate how many strokes it would take to achieve various types of linework. For every drawn line, the craftsman had to make a minimum of two strokes on both sides of the line to remove the wood. In particular, the cross-hatching technique that was used to create a shading effect is difficult and time-consuming to execute. In order to make four lines that cross each other, a woodcutter was obliged to make at least seventy-two strokes to remove all the diamond-shaped spaces in between. To accomplish intricate cutting, a woodcutter needed to constantly assess, intuitively instead of deliberately, the depth of the cutout areas and strokes to form the line work throughout the whole process (figs. 10–12).

Fig. 10. Lychnis, Pietro Andrea Mattioli, Commentarii in sex libros Pedacci Dioscoridis (1565), Dumbarton Oaks Rare Book Collection.

Fig. 11. Mattioli woodblock of Lychnis, Dumbarton Oaks Rare Book Collection.

Fig. 12. Detail of Mattioli woodblock of Lychnis, Dumbarton Oaks Rare Book Collection. The curved part of the leaf shows advanced craftsmanship in woodcutting. The draftsman used short lines to imitate the furry texture on the leaf and cross-hatching to create shadow behind the tip of the leaf. To cut the lines, the woodcutter would need to carefully cut around all the short lines, instead of simply removing the entire area with a gouge or a similar tool. The cutter also removed the little diamond-shaped spaces in the cross-hatched shadow without making the lines seem broken or rigid. These skillful details speak to the cutter’s ability to present organic linework with precise and clean cutting.

Remaking Mattioli’s Imperatoria Woodblock

For the exhibition, an unfinished reproduction of the Imperatoria woodblock is made available for visitors to touch and explore. The reproduction shows several stages of the cutting process to explain the woodcutting technique and provides a tactile complement to the experience of seeing the printed pages. Making this reproduction entailed extensive reading of historical sources on early modern relief printing and experimenting with different types of wood and cutting techniques. This empirical research method, called historical remaking, enables the researcher to study the practical challenges and other aspects that are usually not documented in texts. It helps the researcher generate questions and better understand the processes of how an image was made and reproduced in the early modern period.

The reproduced block has a cruder quality of linework and is shallower in the depth of the removed areas when compared to the original. It shows the handiwork of the researcher and cutter who has yet to master the craft of woodcutting. However, in addition to the level of the researcher’s skill and experience, many factors that would affect the quality of cutting remain unknown. For example, the metal composite of a woodcutting knife and the way in which plane woodblocks were prepared in the early modern period require further research.

Jessie Wei-Hsuan Chen is a PhD candidate in the Department of History and Art History at Utrecht University and a 2020 Stacy Lloyd III Fellow for Bibliographic Study at the Oak Spring Garden Foundation. Her dissertation project investigates the artistic and knowledge production of painted and printed flower books from Germany and the Low Countries in the long seventeenth century (ca. 1575–1725). Chen’s research intersects with topics in the history of art, science, and the book. Applying the concepts of “making and knowing” and “learning by doing,” she engages with historical reworking/ remaking as an empirical way to inquire into the production of images of the plant world. In 2019, she participated in the Plant Humanities summer program at Dumbarton Oaks. Chen serves on the advisory committee for the woodblock digitization project at the Museum Plantin-Moretus in Antwerp and has contributed to exhibitions related to the depictions and uses of plants.

Jessie Wei-Hsuan Chen is a PhD candidate in the Department of History and Art History at Utrecht University and a 2020 Stacy Lloyd III Fellow for Bibliographic Study at the Oak Spring Garden Foundation. Her dissertation project investigates the artistic and knowledge production of painted and printed flower books from Germany and the Low Countries in the long seventeenth century (ca. 1575–1725). Chen’s research intersects with topics in the history of art, science, and the book. Applying the concepts of “making and knowing” and “learning by doing,” she engages with historical reworking/ remaking as an empirical way to inquire into the production of images of the plant world. In 2019, she participated in the Plant Humanities summer program at Dumbarton Oaks. Chen serves on the advisory committee for the woodblock digitization project at the Museum Plantin-Moretus in Antwerp and has contributed to exhibitions related to the depictions and uses of plants.