When a Tlaxcalteca-Spanish expedition arrived at Tenochtitlan on a foggy day in November 1519, the city’s health concerns increased. People were alarmed by the insalubrious appearance of the Spanish visitors. Sweat, dirt, pomander—the city inhabitants were shocked by the foreigners’ filth and stench.

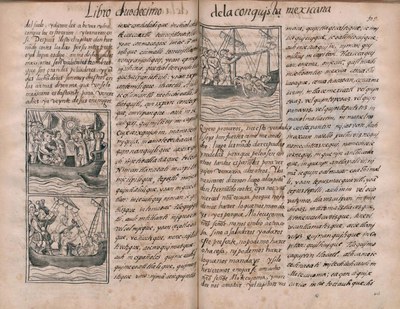

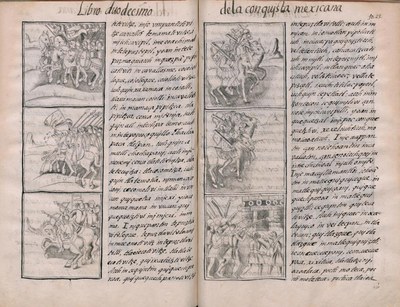

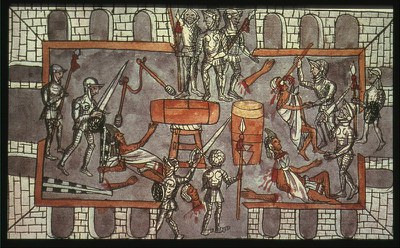

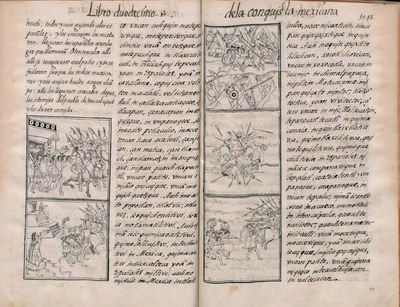

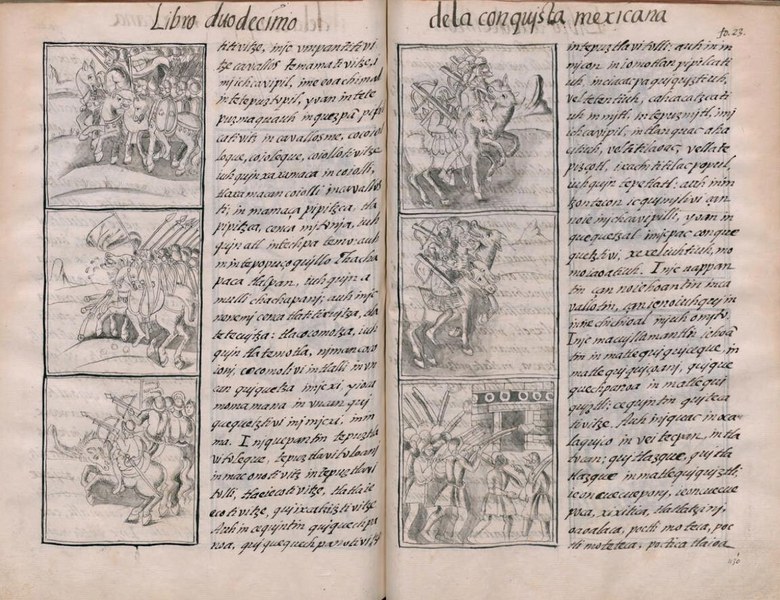

These images detail the alarming sensorial experience elicited by the Spanish arrival. The Nahuatl text explains that the visitors “came stirring up dust, with their faces all covered with earth and ash, full of dirt, wrapped in dust, dirty.” The horses sweated so much that “water seemed to fall from them, and their flecks of foam splatted on the ground.” Spanish weapons emitted smoke of a “very foul stench” and their “fetid smell made people dizzy and faint” (Dufendach 2017:189–91). The Spanish translation omits most descriptions of filth, focusing instead on the expedition’s haste and weaponry. The accompanying images, drawn by Indigenous informants, present the conspicuous filth, detailing spit and dust from horses (middle left), and the pungent clouds of smoke emanating from Spanish weapons (bottom right).

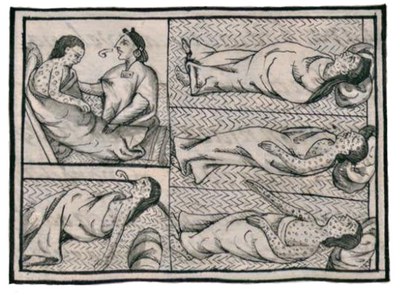

For centuries, Mesoamericans considered bad smells baneful. There are records of the Mexica using bad smells as a weapon of war: during the siege of Colhuacan, they threw worms, frogs, fishes, and ducks into a fire and wafted the smoke into the defending city, causing abortions, swelled limbs, and death among its residents. In Nahua mythology, the stench of the corpse of sorcerer Cuexcoch was believed to have killed many. At the time of the Spanish visit, malodorous plants were considered to have detrimental effects on health, like teccizuacalxochitl, a plant that caused the nose to swell. In the Nahua worldview, filth and smells like those emitted by the Spanish were considered toxic and harbingers of disease.

Image Source

- Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, MS Mediceo Palatino 220 (Florentine Codex), book 12, fols. 22v–23r (3:429v–430r). Courtesy of the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana.

Further Reading

- Dufendach, Rebecca. “Nahua and Spanish Concepts of Health and Disease in Colonial Mexico, 1519–1615.” PhD diss., University of California, Los Angeles, 2017.

- Ortiz de Montellano, Bernard R. Aztec Medicine, Health, and Nutrition. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1990.