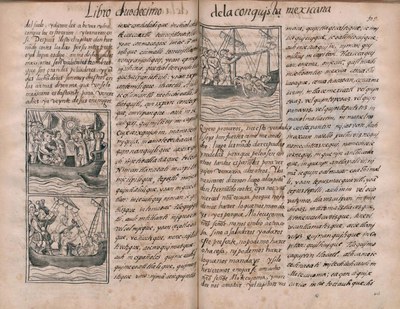

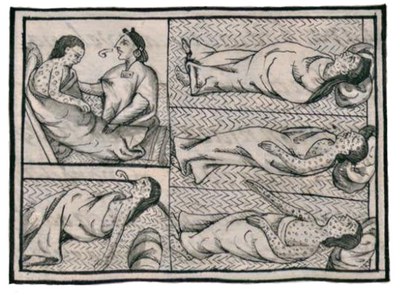

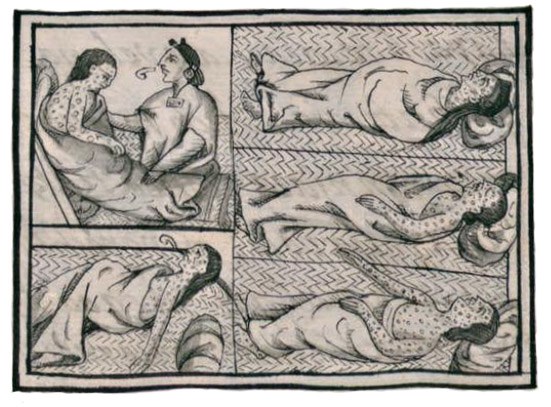

The epidemic that devastated Tenochtitlan in 1520 was identified by residents as hueyzahuatl (great leprosy) and totomonaliztli (pustules)—smallpox. This drawing from the Florentine Codex depicts victims of the disease afflicted by debilitating pustules and excruciating pain. On the top left, a female healer cares for a male victim. On the bottom left, a female victim cries in pain while trying to move. The accompanying text provides a survivor’s harrowing account:

A great plague broke out here in Tenochtitlan . . . striking everywhere in the city and killing a vast number of people. Sores erupted on our faces, our breasts, our bellies; we were covered with agonizing sores from head to foot. The illness was so dreadful that no one could walk or move. The sick were so utterly helpless that they could only lie on their beds like corpses, unable to move their limbs or even their heads. They could not lie face down or roll from one side to the other. If they did move their bodies, they screamed with pain. A great many died from this plague, and many others died of hunger. They could not get up to search for food, and everyone else was too sick to care for them, so they starved to death in their beds. . . . By the time the danger was recognized, the plague was so well established that nothing could halt it. (León Portilla 1992:92–93)

In populations that have not previously been exposed, smallpox can infect almost everyone and kill anywhere from 30 to 100 percent of the infected, depending on the strain. Survivors were permanently scarred and some became blind. Death spread so rapidly that supply networks and services collapsed. Famine ensued, exacerbating mortality. According to the Florentine Codex, “Many died from [the plague], but many died of hunger. There were deaths from starvation, for they had no one left to care for them” (book 12, fol. 53r). Current estimates suggest a population loss of between five and eight million people in the whole of Mesoamerica during the 1520 outbreak.

Image Source

- Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, MS Mediceo Palatino 220 (Florentine Codex), book 12, fol. 53v (3:460v). Courtesy of the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana.

Further Reading

- Acuna-Soto, Rodolfo, et al. “Megasequía y mega-muerte en México en el siglo XVI.” Revista Biomédica 13, no. 4 (2002): 289–92.

- Cook, Noble David. Born to Die: Disease and New World Conquest, 1492–1650. New Approaches to the Americas. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- León Portilla, Miguel. The Broken Spears: The Aztec Account of the Conquest of Mexico. Boston: Beacon Press, 1992 (1962).

- Sandine, Al. “Micro-Invaders.” In Deadly Baggage: What Cortes Brought to Mexico and How It Destroyed the Aztec Civilization, 154–65. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2015.